ZKP Notes

\newcommand{\bm}[1]{\boldsymbol{#1}}

Berkeley Workshop

The reason ZKPs are not a paradox is really because of timing. Well, timing and randomness. While it is true that a verifier could just spit out a transcript of a valid ZKP interaction, the prover is different in that it makes a commitment before the randomized challenge.

But you can turn an interactive proof into a non-interactive one with Fiat Shamir (make the challenge a hash of a commitment).

Interactive Proofs

- common trick

- extend functions to multilinear polynomials.

- rely on the fact that if polynomials are different, they differ in most places (strong statistically guarantees)

- arithmetic circuit

- encode boolean gates as arithmetic, forming an injection to a field

Probabilistically Checkable Proofs

- Verifier as efficient as possible

- Assume prover is computationally powerful

- Interaction not always feasible

- Ideas:

- What if the verifier selects random bits of the proof to verify?

- In this case, increase soundness by increasing # of bits to check

- What if the verifier selects random bits of the proof to verify?

Succinct Arguments

Motivation

Looking at arguments instead of proofs:

- why?

- they can be succinct

- proofs have computational limitations

- e.g. SAT prover/verifier requires in bits

- soundness is computational and applies to efficient provers

- interactive proofs (IP) are a subset of interactive arguments (IA)

Definition

- Define to be a universal relation about all satisfiability problems together:

- is an algorithm,

- an input,

- a time bound

- a witness

- An interactive argument for is succinct if

- communication complexity is small:

- verification time is small:

- verifier has to read the input!

- typically

Construction

We'll use a classical construction from 80s, to transform any PCP (Probabilistically Checkable Proof?) into a succinct argument:

- Theorem: has good PCPs

- proof is not too big

- time to verify it is not too big

- communication is not too big

- First attempt:

- Verifier sends random to sample

- Prover restricts to sample according to

- Verifier verifies according to

- This isn't correct! Prover shouldn't know ahead of time! Prover should commit to their proof ahead of time.

- Upgrade to:

- Prover has to commit to first via a merkle-tree built with a collision-resistant hash function.

- Verifier samples some hash function (can't let prover choose it!).

- Prover builds a merkle tree of its proof, and sends the root of the tree.

- Then verifier sends random .

- Prover deduces the query set and computes paths for locations in .

- sends to verifier

- Verifier

- check paths w.r.t.

- decides according to .

Non-interactive

When we want to make Succinct NonInteractive Arguments (SNARGs), instead of the verifier sending random to the prover, there is an initial Setup phase which outputs a Reference String. So lets remove the interactive bits above:

- Setup phase can choose the hash function for the Merkle tree

- Setup phase can generate a hash for a Fiat-Shamir transform

- Now the interactive is substituted with .

ZK Whiteboard Sessions

Module 1

A SNARK is just a way to prove a statement:

- Succinct Non-interactive Arguments of Knowledge

- basically a short proof (few KB) that is quick to verify (few ms)

A zk-SNARK is a SNARK but it doesn't reveal why the statement is true

Building blocks

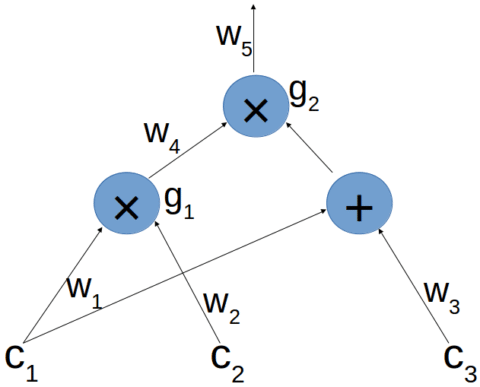

- Arithmetic circuits: Given a finite field , a circuit defines an -variate polynomial with an evaluation recipe in the form of a DAG, where inputs are labeled and internal nodes are labeled .

- e.g. iff .

- Argument system: Given public arithmetic circuit , public statement , and secret witness , suppose we have two parties (V) verifier and (P) prover. An argument system consists of various messages passed between these parties, where P wants to convince V that there does exist such that , but P only sends , not . Then V accepts or rejects P's argument.

- Non-interactive preprocessing argument system: An argument system augmented with a preprocessing step that produces public parameters. Then P has inputs and V has inputs . P then sends a single proof message and V accepts or rejects it. This argument system is defined by the three algorithms:

- .

- .

- .

- We require:

- Completeness: if , always accepts.

- Soundness: if accepts, then knows ; if does not know , then probability of acceptance is negligible. (Note: this is not a logically sound definition. I assume the speaker intended the converse of the former.)

- Zero-Knowledge (optional): reveal nothing about .

- Succinct Non-interactive preprocessing argument system: Further restriction that

- produces short proof:

- is fast:

- Note: these requirements are exactly why we need a preprocessing step; otherwise the verifier would have to read the entire circuit to evaluate it.

- Arithmetic circuits: Given a finite field , a circuit defines an -variate polynomial with an evaluation recipe in the form of a DAG, where inputs are labeled and internal nodes are labeled .

Types of preprocessing steps:

- trusted setup per circuit: where random must be kept secret from prover (otherwise it could prove false statements!)

- trusted but universal (updatable) setup: secret is independent of :

- where

- is a one-time trusted procedure to generate public params; afterwards throw away

- can then be used to deterministically preprocess any new circuits without any dangerous secret randomness

- transparent: S(C) does not use secret data, and there is no trusted setup. This is obviously preferrable.

- E.g.

- Groth'16: small proofs 200B, fast verifier time 3ms, but trusted setup per circuit

- Plonk/Marlin: small proofs 400B, fast verifier time, 6ms , but universal trusted setup

- Bulletproofs: larger proofs 1.5KB, verifier 1.5s, but no trusted setup.

A SNARK software system

- Typically a DSL is used to compile a circuit from a higher level language

- Then public params are generated from the circuit.

- Finally, a SNARK backend prover is fed and also to generat a proof.

Some more formal definitions:

- The formal definition states that is knowledge sound for a circuit if:

- If an adversary can fool the verifier with non-negligible probability,

- then an efficient extractor which interacts with the adversary as an oracle, can extract with the same probability.

- (If knows , then can be extracted from .)

- is zero knowledge if

- there is an efficient algorithm such that

- looks like the real and .

- notice the simulator has more power than the prover - it can choose !

- (If for every , the proof reveals nothing about other than existence.)

- The formal definition states that is knowledge sound for a circuit if:

Module 2

zk-SNARK is generally constructed in two steps:

- A functional commitment scheme, and

- (cryptography happens here)

- A suitable interactive oracle proof (IOP)

- (information theoretic stuff happens here)

- A functional commitment scheme, and

A commitment scheme is essentially an "envelope". Commit to a value and hide it in the envelope.

- It consists of two algorithms

-

- is random

- is small even for large , typically 32B

-

- Satisfying properties:

- binding: cannot produce two valid openings for a single commitment .

- hiding: the reveals nothing about the committed data (envelope is opaque!)

- Example: hash function

- It consists of two algorithms

We actually commit to a function , where is a family of .

- Prover commits to and sends to verifier.

- Verifier sends

- Prover sends and proof which proves and .

A functional commitment scheme for :

- outputs public params (one time setup)

-

- SNARK requires binding

- zk requires hiding

- for given :

Examples

- KZG:

- where is a polynomial

- a trusted setup defines around an that is thrown out afterwards.

- commitments are simple algebraic operations around

- proofs are literally single elements from a group

- verifier is a constant time assertion of element equality using a tiny bit of public params.

- very elegant, aside from trusted setup.

- Dory:

- Removes trusted setup from KZG at the cost of:

- proof size

- prover time $O(d)

- verify time $O(log d)

- Removes trusted setup from KZG at the cost of:

- KZG:

Module 3

Let be a primitive -th root of unity. Set

Let

- Gadgets: There are efficient poly-IOPs for:

- zero test: is identically zero on .

- sum-check:

- product-check:

All of these are rather simple constructions relying on the fact that polynomials have highly unique outputs: consider the probability that a random is a root of . Out of possible values for , has at most roots, so the probability is . If and , this is negligible.

PLONK poly-IOP for general circuit

- First, prover compiles a circuit to a computation trace. The computation trace is just a representation of the inputs at each of the gates.

- To encode as polynomial ,

- let be total # of gates in C,

- be the total # of inputs.

- Encode gates as:

- : left input of gate

- : right input of gate

- : output of gate

- To encode as polynomial ,

- Then, prover will prove

- encodes correct inputs

- every gate evaluated correctly

- wiring is implemented correctly (basically means equal values from one gate output get sent to the next gate correctly)

- output of last gate is zero: .

These steps are detailed below:

- To prove correct inputs:

- Both prover and verifier interpolate a polynomial that encodes the inputs to the circuit.

- input # j.

- So all the points encoding the input are

- Hence prover can prove (1) with a zero test: for all .

- Both prover and verifier interpolate a polynomial that encodes the inputs to the circuit.

- To prove gates evaluated correctly, encode gates with a selector polynomial to pick out which ones are addition/multiplication:

- Define selector such that for all :

- if gate # is an addition gate

- if gate # is a multiplication gate

- Then for all gates :

- .

- NOTE: selector only depends on circuit, not input, so it can be computed in the preprocessing step!

- So where is a commitment to the selector polynomial .

- Now proving happens via another zero-test on for all gates .

- Define selector such that for all :

- To prove the wiring is correct, you define a rotation polynomial and then prove for all .

- This is another thing that gets to be precomputed in preprocessing step.

- Important note: has degree and we don't want this to run in quadratic time.

- Instead PLONK uses a cute trick to verify a prod-check in linear time.

- Is trivial

Finally:

- and

- Prover has and wants to prove with witness :

- build the polynomial that encodes the computation trace of the circuit .

- send the verifier a commitment to .

- Verifier builds

- Prover proves the 4 steps above:

- zero test: for all

- zero test: for all

- zero test: for all

- evaluation test:

Theorem: Plonk Poly-IOP is complete and knowledge sound.

- The verifier's params are just polynomial commitments. They can be computed with no secrets.

- Also, we can match up this polynomial IOP with any polynomial commitment scheme. Thus, if we use a polynomial commitment scheme that does not require a trusted setup, we'll end up with a SNARK that does not require trusted setup.

- This SNARK can be turned into a zk-SNARK

Stats:

- Proof size: ~ 400 bytes

- Verifier time: ~ 6ms

- Prover time: computing P is linear in memory, and not tenable for large circuits.

Explaining SNARKs behind Zcash

Homomorphic hiding

This ingredient (informally named!) is essentially a one-way function that is homomorphic over some operation.

Specifically an HH must satisfy:

- Hard to invert to find .

- Mostly injective: .

- Given , one can compute .

For example over , define for a generator . The discrete log problem ensures (1). The fact that is a generator ensures (2). Of course, you can compute to find :

Note: this definition of HH is similar to the well known "Computationally Hiding Commitment", except that it is deterministic.

Blind evaluation of polynomials

Let be defined as above. Note also that we can evaluate linear combinations of hidings:

Suppose Alice has a polynomial of degree over . Bob has a point . Suppose further that Alice wants to hide and Bob wants to hide , but Bob does want to know , a homomorphic hiding of .

We can use a procedure where:

- Bob sends the hidings to Alice.

- Alice computes via:

and sends it to Bob.

This will be useful in the prover-verifier setting when the verifier has some polynomial and wants to make sure that the prover knows it. By having the prover blindly evaluate the polynomial at an unknown point, with very high probability the prover will get the wrong answer if they don't use the correct polynomial. (Again relying on the fact that different polynomials are different almost everywhere.)

The Knowledge of Coefficient Test and Assumption

Another thing we'd like for our protocol is to enforce that Alice actually does send the value , and not some other random value. We need another tool to build that enforcement mechanism: the Knowledge of Coefficient (KC) Test.

Let's work with a group of prime order . Define to be an -pair if and ; note we are still in a group but we're letting denote summing times.

The KC Test is performed via the following steps:

- Bob chooses random and , then computes . He sends Alice the -pair .

- Alice sends back to Bob a different -pair .

- Bob accepts Alice's response only if is indeed an pair. Since he knows , he can simply compute and compare it to .

But how does Alice compute another pair without actually knowing ? It turns out the only reasonable strategy is for her to choose her own random and just compute the multiple of the pair: . Of course

The Knowledge of Coefficient Assumtion (KCA) states that with non-negligible probability, if Alice returns a valid -pair to Bob's challenge, then she knows such that .

We formalize the notion of Alice knowing as follows: define another party called Alice's Extractor which has access to Alice's inner state.

So to formalize the KCA, we can say that if Alice responds successfully with , then Alice's extractor outputs such that (with high probability).

How to make Blind Evaluation of Polynomials Verifiable

As mentioned above, we want to verify that Alice sends the correct value. Let's extend the protocol above.

Now, suppose Bob sends multiple pairs to Alice that are all pairs (i.e. is constant). Now Alice can construct an -pair out of a linear combination of Bob's:

for any chosen . Notice this is still an -pair:

The extended KCA states that if Alice succeeds in sending back an -pair after Bob sends these -pairs, then Alice knows a linear relation between and .

For our purposes, Bob will send -pairs with a certain polynomial structure. The d-Power Knowledge of Coefficient Assumption (d-KCA) is as follows: suppose Bob chooses a random and , and sends Alice the pairs

If Alice successfully outputs a new -pair , then with very high probability, Alice knows some $c_0, \ldots, c_d \in \mathbb{F}pa' = \sum{i = 0}^d c_i s^i \cdot g$.

Now, we can make a protocol that enforces Alice to send the correct value. Let (a homomorphic hiding) for some generator of a group of prime order .

Bob chooses a random . He sends Alice the hidings of

which are

Alice computes and using the elements in the first step, and sends them to Bob. Again, note that she can compute these:

Bob accepts if and only if .

Notice that under the d-KCA, if Bob accepts, then Alice does indeed know some polynomial such that (with high probability).

- Note It's not clear to me at the moment, what's to stop Alice from sending a different linear combination, perhaps of some other polynomial ? Maybe there is no such incentive for her to cheat in this way, but if we want to make sure she's actually sending it seems important.

- This was correct: as seen below, the polynomial she sends must satisfy an equality check to another polynomial, so if she doesn't send the correct value, she fails the protocol.

From Computations to Polynomials

Here we learn how to actually make arithmetic circuits. For an example, suppose Alice wants to prove to Bob that she knows such that .

we encode the field operations as gates, each with two inputs and one output, and we refer to the edges as "wires", which line up which inputs go to which gates. There are some counterintuitive aspects of this circuit:

- wires from a single node are all labeled together as one

- we don't label addition gates

- we don't label wires from addition to multiplication gates; instead are both thought of as right inputs to .

We define a legal assignment to be an assignment of values to the labeled wires, where multiplication holds. E.g. above, any such that and is a legal assignment.

- Note but what about ? These seem to be built-in to the polynomial definitions (they are sums, so as long as e.g. and are non zero, they'll get selected in the QAP below).

Back in our example, Alice can equivalently prove that she knows a legal assignment such that .

Reduction to QAP

For each , we define , , and as left wire polynomials, right wire polynomials, and output wire polynomials respectively. We then define certain constraints via selector polynomials; namely, since we have two gates , we associate them with target points respectively, and then define constraints around the wire polynomials such that those involving gate output one on target point 1, zero elsewhere, and those involving gate output one on target point 2, zero elsewhere:

all other polynomials are set to zero. Next define

Now, we can say is a legal assignment iff vanishes on all target points. Further, we can define a target polynomial, in this case: (basically the smallest polynomial ensuring each target point is a root), and say that we have a legal assignment iff divides .

A Quadratic Arithmetic Program (QAP) Q of degree and size consists of polynomials and target polynomial of degree .

An assignment satisfies if are defined as above (but to instead of 5), and divides .

Bringing this back to Alice, she needs to prove she has an assignment that satisfies the above with .

The Pinocchio Protocol

Now we want to offer a way for Alice to prove that she knows a satisfying assignment (but let's leave off proving the final gate value for now).

Note that divides iff for some polynomial of degree at most . (Recall has degree , , where have degree at most , hence has degree at most , so must have degree at most .)

Again, Schwartz-Zippel Lemma to the rescue, if and are different polynomials, they differ in at most places. As long as , the probability that a random satisfies is negligible when these polynomials are not equal.

Protocol:

- Alice chooses each of degree at most .

- Bob chooses random and computes .

- Note: I think Bob also sends to Alice for step 3.

- Alice uses blind evaluation of the polynomials evaluated at : .

- Bob uses the homomorphic properties of to check that .

There are four more things required to turn this into a zk-SNARK:

- We need to ensure that the come from an actual assignment (are defined as sums with , etc.).

- Ensure zero knowledge is learned from Alice's output.

- Under the simple group hiding , we have only seen homomorphic addition, and haven't yet defined a way for Bob to do homomorphic multiplication (necessary in step 4 of the protocol above).

- Remove interaction from the protocol.

For (1), let . Now the coefficients of do not mix. Similarly for define . Notice this property holds for linear combinations of the :

If is a linear combination of these , then because of the non-mixing of coefficients, it must also be the case that each for each . That is, the are indeed produced by an assignment .

So, Bob can have Alice prove that is a linear combination of 's:

- Bob chooses random and sends Alice .

- Alice must send Bob . Notice that is a linear combination of the , so under the d-KCA, if she succeeds, we can assume that she does indeed know the polynomial coefficients of in terms of .

- Note: based on the above section, I think both parties also need to send values without the constant.

For (2), notice we haven't introduced any randomness yet. So, for example, if Bob were to take a different assignment and compute and hidings , he can determine whether or not . To avoid this, we add random -shifts to each polynomial.

To be specific, Alice will choose random and define

since these are all multiples of , division still holds but with a different quotient:

So, defining , we have a new set of polynomials satisfying . Alice will use these instead. These polynomials mask her values: notice that is nonzero with high probability (if ), so e.g. looks like a random value now.

Pairings of Elliptic Curves

Now let's solve the last parts (3) and (4) necessary for a zk-SNARK.

To build part (3) will inevitably involve material that is not self-contained here. Recall elliptic curves from Intro to Cryptography - Chapter 6. Denote the curve by . Assume is prime not equal to , so that any generates .

The embedding degree is the smallest integer such that . It is conjectured that for , the discrete log is hard in .

The multiplicative group of (recall this is a group of order ) contains a subgroup of order that we denote . Recall $G_1 = \mathcal{C}(\mathbb{F}p)\mathcal{C}(\mathbb{F}{p^k})G_1G_2rr$ such subgroups, but proof not shown in this article).

So to be clear, lives in a typical group of integers (modulo ), and are elliptic curves.

Fix generators . There is an efficient function called the Tate reduced pairing such that

- for a generator of .

- for all .

Now back to our setting, define

and note that each is homomorphic over addition, and we can compute from and . This gives us the multiplicative "kinda homomorphism" that we need to construct, say, from the hidings .

To make this non-interactive, we'll use a (trusted-setup-style) common reference string (CRS) to start. We'll just publish Bob's first message as a CRS. So, to obtain the hiding of Alice's polynomial at Bob's randomly chosen :

Setup: Random are chosen and the following CRS is published:

Proof: Alice computes and using the CRS and the same techniques above.

Verification: Bob computes and verifies equality of and :

Recall under the d-KCA, Alice will only pass this verification check if is a hiding of for some polynomial of degree that she knows. But in this protocol, Bob does not need to know the secret , since he can use the function to compute from .

- Note: what about the Pinocchio protocol involving ? is that involved implicitly at all in this final construction, or does that happen separately?

Bulletproof docs

TODO

Bulletproofs OG

Let $p(X) \in \mathbb{Z}p^n[X]\sum{i =0}^d \textbf{p}_i \cdot X^iq$ similarly. Let's make sure the multiplication definition makes sense:

$$ \begin{align*} p(x) = \textbf{p}0 + \textbf{p}1\cdot x + \cdots + \textbf{p}d \cdot x^d &= \begin{bmatrix} p{0,0} \\ \vdots \\ p{0, n} \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} p{1,0} \cdot x \\ \vdots \\ p_{1, n} \cdot x \end{bmatrix} + \cdots + \begin{bmatrix} p_{d,0} \cdot x^d \\ \vdots \\ p_{d, n} \cdot x^d \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} p_{0,0} + p_{1,0}\cdot x + \cdots + p_{d,0} \cdot x^d \\ \vdots \\ p_{0, n} + p_{1, n} \cdot x + \cdots + p_{d, n} \cdot x^d \end{bmatrix} \\ &= \begin{bmatrix} p_0(x) \\ \vdots \\ p_n(x) \end{bmatrix}\end{align*}$$

So this is rather simple, even though the Bulletproofs paper makes a rather complicated definition. (I'm not even sure their inner product definition is correct. It looks wrong.) is just a vector whose entries are each degree polynomials over the same discriminate. An inner product between such vector polynomials is just a sum over the entry-wise polynomial multiplication. (Hadamard would similarly be defined as just entry-wise polynomial multiplication.)

ZKSummit

logUp: lookup arguments via log derivative

- Multiset equality:

- Note: sequences and are permutations of one another iff over .

- Set membership: the set of is contained in the set of iff there exists such that over

- Interopability criterion: some clever subset relation with really, really poor mathematical notation and no explanation. It has something to do with the "derivative" which is the difference between consecutive sequence elements and multiplicative factors of a lookup table.

Recall logarithmic derivative

we want this because it turns products into sums:

notice that with roots in the denominator, roots are turned into poles, with multiplicities maintained.

There is some accounting and helper functions necessary to batch these operations, but in the end you get a sum of polynomials that don't blow up in degree like they do in "PLookup".

trustlook dark pools via zk

- Current problems: large token movements create hysteria

- Dark pools keep such movements private until things settle down (like a commitment)

- Formally allowed by US under 6% GDP

- Prior work

- DeepOcean

- accountability of matchmaking service

- not compatible with decentralized markets

- Renegade.fi

- is compatible, but requires separate p2p messaging layer to operate

- NOTE this is a similar complaint to what we'd be doing with side-car IPFS

- is compatible, but requires separate p2p messaging layer to operate

- DeepOcean

teaching ZKPs

This isn't really about teaching ZKPs, this is more someone just teaching (basics of) ZKPs well. Some of the notable simplifications:

- Completeness: verifier convinced

- Soundness: prover can't cheat

- Lookup tables come into play because "looking up in memory" does not play nice with arithmetic circuits. To ensure the prover doesn't cheat, merkle trees are used.

linear algebra and zero knowledge

nice talk about generalizing common checks in terms of linear algebra equations

Short Discrete Log Proofs

An FHE ciphertext can be written as:

where is the public key, is the message and randomness, and is the ciphertext. The vector space is over a polynomial ring for some integer and monic irreducible polynomial of degree . This paper details a protocol for proving knowledge of , and also proving the coefficients are in the correct range. This can be combined with existing ZKPs for discrete logarithm commitments to prove arbitrary properties about .

Overall strategy

- Create a joint Pedersen commitment to all coefficients in .

- ZKP that

- those coefficients satisfy .

- coefficients comprise valid RWLE ciphertext

- Use existing ZKPs for discrete log commitments to prove arbitrary properties about .

Protocol overview

Setting

The first statement we prove is a simpler representation:

where $\bm{a}_i, \bm{s}_i, \bm{t} \in \mathcal{R}q|s{ij}| \le BGp \le 2^{256}$ where discrete log is hard.

Step 1

The prover first rewrites this statement to move from to :

$$

\sum_{i = 1}^m \bm{a}_i \bm{s}_i = \bm{t} - \bm{r}_1\cdot q - \bm{r}_2 \cdot \bm f

$$

for some polynomials that are of small degree with small coefficients.

Step 2

Prover creates Perdersen commitment where each integer coefficient of is in the exponent of a different generator , and sends to Verifier.

Step 3

Verifier sends challenge . The prover sends a proof back, consisting of:

- Range proof that proves committed values in are all in correct ranges.

- Proof that the polynomial () evaluated at holds over .

Note that because (1) proves the coefficients are sufficiently small, and because , the polynomial evaluation in (2) should not have had any reduction modulo ; thus it also holds over , completing the proof.

We will show (2) in detail and then how to combine (1) and (2).

Step 3(a)

Define

$$

\begin{align*}

U &= [\bm a_1(\alpha) \cdots \bm a_m(\alpha) q \bm f(\alpha) ] \mod p

\\S &= \matrix{\bm s_1 }

\end{align*}

$$

TODO finish section

TODO: IPP: p16-17

TODO: main algorithm: p22

- slight deviation: instead of computing scalar multiplications at each stage, you compute a giant MSM at the end via Pippengers.

Questions

Is this related to our task of "supporting mixed bounds"?

Due to the fact that the ranges of the and are different, storing these in the same matrix would require us to increase the size of the matrix to accommodate the largest coefficients

- , even smaller

- Yes!

- We want to break up even smaller to be more efficient

- Instead of breaking up each coefficient of to the same number of bits, they get broken up into different number of bits.

- 18 is largest noise for fresh ciphertext

- Stale ciphertext: probably , ideally power of .

Is this our "gluing proofs together" task? Or is this still strictly "logproof" and we have something totally separate outside of SDLP that we glue to it?

Combining the two proofs and into one.

- No!

- SDLP shows: (1) and (2) on its own. It is both of these proofs.

- The "proving arbitrary properties via aforementioned very efficient ZKPs for discrete logarithm commitments" is what we're doing by gluing in bulletproofs.